Hulk Hogan

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (July 2025) |

Hulk Hogan | |

|---|---|

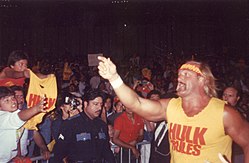

Hogan in 1985 | |

| Born | Terry Gene Bollea August 11, 1953 Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | July 24, 2025 (aged 71) Clearwater, Florida, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1977–2025 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | |

| Relatives | Horace Hogan (nephew) |

| Ring name(s) | Hollywood Hogan[1] Hollywood Hulk Hogan[2] Hulk Boulder[3] Hulk Hogan[4] Hulk Machine[5][2] Mr. America[2] Sterling Golden[6] Terry Boulder[2] The Super Destroyer[2] |

| Billed height | 6 ft 7 in (201 cm)[4] |

| Billed weight | 302 lb (137 kg)[4] |

| Billed from | Hollywood, Los Angeles (as Hollywood Hogan) Venice Beach, California[4] (as Hulk Hogan) Washington, D.C. (as Mr. America)[7] |

| Trained by | Hiro Matsuda[2] |

| Debut | August 9, 1977 |

| Retired | January 27, 2012 |

| Website | hulkhogan |

| Signature | |

| |

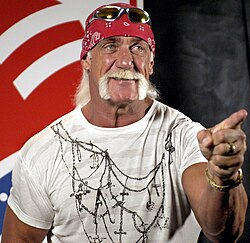

Terry Gene Bollea[8][9] (/bəˈleɪə/; August 11, 1953 – July 24, 2025), better known by his ring name Hulk Hogan, was an American professional wrestler and media personality. Hogan was widely regarded as one of the greatest and globally most recognized wrestling stars of all time.[10][11] He won multiple championships worldwide, most notably being a six-time WWF Champion. He is best known for his work in the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE) and World Championship Wrestling (WCW). He also competed in promotions such as Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA), the American Wrestling Association (AWA), and New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW).[12][13]

Known for his showmanship, large physique, and trademark blond American Fu Manchu[14] moustache[15] and bandanas, Hogan began training in 1977 with Championship Wrestling from Florida and achieved global stardom after joining the WWF in 1983. His heroic, all‑American persona helped usher in the 1980s professional wrestling boom, during which he headlined eight of the first nine editions of WWF's flagship annual event WrestleMania and regularly headlined Saturday Night's Main Event. His first reign as WWF Champion lasted 1,474 days—the third-longest in the title’s history[a]—and he became the first wrestler to win back-to-back Royal Rumbles in 1990 and 1991.[17]

In 1994, Hogan joined WCW and won the WCW World Heavyweight Championship six times. His reinvention as the villainous Hollywood Hogan and leadership of the New World Order (nWo) revitalized his career and significantly contributed to the success of the "Monday Night War" wrestling boom of the late 1990s, including three headline appearances at Starrcade.[18] Hogan returned to WWF in 2002—after WWF acquired WCW—winning the Undisputed WWF Championship for a then-record-equalling sixth reign before departing in 2003.[19] He was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2005 and a second time in 2020 as part of the nWo.[20]

Outside wrestling, Hogan appeared in films such as Rocky III, No Holds Barred, and Suburban Commando, and starred in television shows including Thunder in Paradise and Hogan Knows Best. He also fronted the Wrestling Boot Band; their sole record, Hulk Rules, reached number 12 on the Billboard Top Kid Audio chart in 1995.[21]

Several controversies damaged Hogan's public image. In 1994, he admitted to using anabolic steroids since 1976, and helping stop a wrestling unionization effort. In 2012, the media company Gawker published portions of a sex tape in which Hogan was heard using racial slurs. Hogan sued Gawker, which was found liable and subsequently declared bankruptcy. Despite this legal victory, Hogan's reputation has been described as "permanently tarnished", a view reflected in the mixed public reaction to his death in July 2025.[22]

Early life

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

Hogan was born in Augusta, Georgia, on August 11, 1953,[2] the son of construction foreman Pietro "Peter" Bollea (December 6, 1913 – December 18, 2001) and homemaker and dance teacher Vernice "Ruth" (née Moody; January 16, 1920 – January 1, 2011). Hogan was of Italian, Panamanian, Scottish, and French descent;[23] his paternal grandfather, also named Pietro, was born in 1886 in Cigliano, Province of Vercelli in Piedmont.[24] Hogan had an older brother named Allan (1947–1986) who died at the age of 38 from a drug overdose.[25] When he was one and a half years old, his family moved to Port Tampa, Florida.[26] As a boy, he was a pitcher in Little League Baseball. Hogan attended Robinson High School.[27] He began watching professional wrestling at 16 years old. While in high school, he revered Dusty Rhodes,[28] and he regularly attended cards at the Tampa Sportatorium. It was at one of those wrestling cards where he first noticed "Superstar" Billy Graham and began looking to him for inspiration;[28] since he first saw Graham on TV,[28] Hogan wanted to match his "inhuman" look.[28]

Hogan was also a musician, spending a decade playing fretless bass guitar in several Florida-based rock bands.[1] He went on to study at Hillsborough Community College and the University of South Florida. After music gigs began to get in the way of his time in college, he dropped out of the University of South Florida.[29] Eventually, Hogan and two local musicians formed a band called Ruckus in 1976.[30] The band soon became popular in the Tampa Bay region.[30] During his spare time, Hogan worked out at Hector's Gym in the Tampa Bay area, where he began lifting.[31] Many of the wrestlers who were competing in the Florida region visited the bars where Ruckus was performing.[28] Among those attending his performances were Jack and Gerald Brisco.[28]

Professional wrestling career

Early years (1977–1979)

Jack and Geraldo Brisco got Hogan connected with Hiro Matsuda—the man who trained wrestlers working for Championship Wrestling from Florida (CWF)—to make him a potential trainee.[32] During the first session in training, Matsuda broke Hogan's leg. After 10 weeks of rehab, Hogan returned to train with Matsuda and blocked him when he tried to break his leg again.[33] In Hogan's professional wrestling debut, CWF promoter Eddie Graham booked him against Brian Blair in Fort Myers, Florida, on August 10, 1977.[34][35] A short time later, Hogan donned a mask and assumed the persona of "The Super Destroyer", a hooded character previously played by Don Jardine and subsequently used by other wrestlers.[36]

After a brief career hiatus, Hogan wrestled for the Alabama-based promotion Gulf Coast Championship Wrestling (GCCW) in 1978. He formed a tag team with Ed Leslie known as The Boulder Brothers under the names Terry and Ed Boulder.[37] During his time in Alabama, Hogan had early encounters with André the Giant, including two matches and a televised arm-wrestling contest that generated significant local interest.[38][39] On May 24, 1979, Hogan wrestled his first world championship match against NWA World Heavyweight Champion Harley Race at Rip Hewes Sports Complex in Dothan. Hogan pinned Race during the match and was briefly announced as the new champion on GCCW television. However, the NWA later overturned the decision, declaring a disqualification and nullifying the title change.[40][41] Hogan went on to win the Southeastern Heavyweight Championship twice later in the year; first defeating Ox Baker, then again after regaining it from Professor Tanaka, following a brief loss to Austin Idol.[citation needed]

Later that year, Hogan and Leslie joined Jerry Jarrett's Memphis-based Continental Wrestling Association (CWA) in Memphis promotion.[42] While in Memphis, Hogan made a talk show appearance alongside actor Lou Ferrigno, star of the television series The Incredible Hulk.[43] The host commented that Hogan, standing 6 ft 7 in (201 cm) and weighing 295 lbs (134 kg) with 24-inch (61 cm) biceps, dwarfed Ferrigno. Inspired by this, Mary Jarrett suggested the nickname "The Hulk," resulting in Hogan wrestling as Terry "The Hulk" Boulder.[44] He also occasionally also performed under the name Sterling Golden.[1]

World Wrestling Federation (1979–1981)

According to his autobiography My Life Outside the Ring, Bollea briefly left professional wrestling in 1979 and was working on the Tampa docks when he was spotted by Gerald Brisco. Brisco and his brother encouraged Hogan to return to wrestling and helped arrange a meeting with World Wide Wrestling Federation promoter Vince McMahon Sr.[45] However this claim is disputed, with some wrestling historians crediting Terry Funk with recommending Hogan to McMahon Sr., having recognized his potential during Hogan's early matches.[46][47]

McMahon was impressed with Bollea's charisma and physical stature, offered him a spot on the WWWF roster as an opponent for André the Giant. McMahon, who wanted to use an Irish name, gave him the last name Hogan, and suggested he dye his hair red. Hogan, whose hair was already thinning, declined, quipping, "I'll be a blond Irishman."[48] Hogan wrestled his first match in the WWWF under the ring name "Hulk Hogan" by defeating Harry Valdez[49] on the November 17 episode of Championship Wrestling. He was presented as a villain in the WWWF, and was managed by "Classy" Freddie Blassie.[50]

The next year, Hogan began a high-profile feud with André the Giant. On August 9, 1980, at Showdown at Shea, André defeated Hogan in a match.[51][52] However, Hogan notably body-slammed André during the bout, an early version of the iconic moment that would later be immortalized at WrestleMania III.[53] They faced off again on August 30, 1980, at Madison Square Garden in a televised match with Gorilla Monsoon serving as special guest referee. Once again, Hogan managed to body-slam André, but was unsuccessful in ultimately defeating him.[54]

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (1980–1985)

In 1980, Hulk Hogan began wrestling for New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW), where he was nicknamed "Ichiban" (一番; "Number One"). by Japanese fans. He made his debut on May 13, 1980, while still under contract with the WWF, and continued to tour Japan occasionally over the next few years. During his time in NJPW, Hogan used a more technical wrestling style, than his usual power-based approach he performed with in the U.S. He also used the Axe Bomber, a crooked arm lariat, as his finisher in Japan instead of his usual finisher the running leg drop.

While still appearing for the WWF, including Pedro Morales for the Intercontinental Championship in March 26, 1981,[55] Hogan achieved major success in Japan. On June 2, 1983, he won the inaugural International Wrestling Grand Prix (IWGP) tournament by defeating Antonio Inoki by knockout, becoming the first holder of the original version of the IWGP Heavyweight Championship.[56][57] Hogan also teamed with Inoki to win the MSG Tag League tournament in both 1982 and 1983.[citation needed] In 1984, Hogan returned to NJPW to defend the IWGP title against Inoki, who had earned a title shot by winning that year's IWGP League.[57] Hogan lost the match and therefore the title by countout after interference from Riki Choshu.[citation needed] During this period, Hogan also defended his WWF World Heavyweight Championship in Japan against opponents like Seiji Sakaguchi and Tatsumi Fujinami. His final match of that tour was on June 13, 1984, where he again lost to Inoki by countout in an IWGP title match. Hogan was the only IWGP champion to defend the title without winning the qualifying tournament.[58][57]

American Wrestling Association (1981–1983)

After accepting a role in Rocky III, a decision that led to Vincent J. McMahon releasing him from the WWF, Hogan joined the American Wrestling Association (AWA), owned by Verne Gagne, in August 1981. He initially debuted as a villain managed by "Luscious" Johnny Valiant, but quickly became a fan favorite due to his charisma and popularity with the crowd. Hogan soon began feuding with the villainous Heenan Family and Nick Bockwinkel.[59] His official turn to a hero occurred in mid-1981 during a televised segment where he saved Brad Rheingans from an attack by Jerry Blackwell. This sparked a feud with Blackwell, which Hogan eventually won, leading to his first title matches against Bockwinkel by the end of the year.[59]

In March 1982, Hogan defeated Bockwinkel and his manager Bobby Heenan in a non-title handicap match in the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois. He repeatedly challenged Bockwinkel for the AWA World Heavyweight Championship, with most of their matches ended in disqualification, preventing a title change. In April 1982, Hogan seemingly won the championship in St. Paul, Minnesota, but the decision was later overturned by AWA President Stanley Blackburn due to the use of a foreign object..[60][61][62]

Hogan introduced the term "Hulkamania" during a May 15, 1982 appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.[63] Following his role in Rocky III, "Hulkamania" gained widespread popularity.[64] It was also during his time in the AWA that Hogan would first claim "Hulkamania is running wild," a recurring catchphrase of his over his career.[65]

Despite his growing popularity, Gagne resisted making Hogan the AWA World Champion, preferring traditional wrestling over Hogan's flamboyant entertainment-driven style.[66] Gagne later agreed to have Hogan win the title at AWA's Super Sunday event on April 24, 1983, but only if Hogan gave him the majority share of his merchandise and earnings in New Japan Pro-Wrestling.[67] Hogan declined, offering only a 50/50 split, and Gagne withheld the championship.[67] Whilst Hogan still pinned Bockwinkel at Super Sunday, the decision was reversed later that night. After further unsuccessful title attempts, a storyline teased Hogan leaving the promotion..[68] However he returned on July 31, 1983, wearing an "American Made" shirt and focusing on a new feud with Masa Saito.[69]

Later that year, Vince McMahon Jr. secretly visited Hogan in Minneapolis and offered him a leading role in the WWF. Hogan accepted and abruptly left the AWA in November 1983, reportedly sending his resignation by telegram. Gagne initially believed it was a prank until he realized Hogan was not showing up for AWA shows.[59] In his memoir My Life Outside the Wrestling Ring, Hogan stated that he left because McMahon promised him the WWF Heavyweight Championship and a key role in expanding the company nationally.[70]

Return to WWF (1983–1993)

Rise of Hulkamania (1983–1984)

After purchasing the WWF from his father in 1982, Vincent K. McMahon planned to expand the company into a national promotion and selected Hulk Hogan as its top star, citing his charisma and widespread recognition. Hogan returned to the WWF at a television taping in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 27, 1983, defeating Bill Dixon.[71]

On the January 7, 1984 episode of Championship Wrestling, Hogan solidified his status as a fan favorite by rescusing Bob Backlund from an attack by the Wild Samoans.[72] On January 23, 1984, Hogan won his first WWF World Heavyweight Championship by defeating The Iron Sheik at Madison Square Garden, becoming the first wrestler to escape the Sheik's finishing move, the camel clutch, in the process.[73]

Following his victory, commentator Gorilla Monsoon famously declared, "Hulkamania is here!" Hogan quickly became the face of the WWF, referring to his fans as "Hulkamaniacs" and promoting his "three demandments": training, saying prayers, and eating vitamins. A fourth, "believing in yourself," was later added during his 1990 feud with Earthquake. Hogan’s ring attire adopted a red-and-yellow color scheme, and his entrances featured him tearing his shirt, posing, and encouraging the crowd to cheer.

His matches during this period often followed a formula: after an initial offense, he would appear to be on the verge of defeat after being beaten down by his opponent, before “Hulking up” drawing on crowd energy to make a sudden comeback. This would be then followed by his signature sequence of moves: finger-pointing, punches, an Irish whip, the big boot and running leg drop to secure victory.[74]

In 1984, similarities between Hogan and Marvel Comics’ Incredible Hulk led to a legal agreement. Titan Sports, Marvel, and Hogan signed a deal granting Marvel the trademarks to "Hulk Hogan," "Hulkster," and "Hulkamania" for 20 years. As part of the agreement, the WWF could no longer refer to Hogan as “The Incredible Hulk,” “Hulk,” or use purple and green in his presentation. Marvel also received 0.9% of Hogan-related merchandise revenue, $100 per match, and 10% of Hogan’s other earnings under the name.[75][76] This agreement would carry over into Hogan's time in WCW, which by 1996 had become a sister company to Marvel rival DC Comics through their parent company Time Warner. However, Hogan was using the "Hollywood Hogan" persona at that time, avoiding potential legal conflicts. In reference to the dispute, a story in 1988's Marvel Comics Presents #45 had a panel where a wrestler resembling Hogan was tossed through an arena roof by the Incredible Hulk as he had "picked the wrong name." [77]

International renown (1985–1988)

Over the following year, Hulk Hogan became the face of professional wrestling as Vince McMahon expanded the WWF into mainstream pop culture through the Rock 'n' Wrestling Connection on MTV, This period saw large increases in viewing attendance, television ratings, and pay-per-view buys. Hogan was the main attraction at the first WrestleMania, held on March 31, 1985, where he teamed with actor and wrestler Mr. T to defeat "Rowdy" Roddy Piper and "Mr. Wonderful" Paul Orndorff.

Hogan made multiple successful title defenses throughout 1986, including against King Kong Bundy at WrestleMania 2, and in the fall he occasionally wrestled in tag team matches with The Machines as Hulk Machine under a mask copied from NJPW's gimmick "Super Strong Machine".[2][78] At WrestleMania III in 1987, Hogan defended his title against André the Giant, whom the WWF promoted as undefeated in the WWF for 15 years.[79] André turned heel by aligning with manager Bobby "The Brain" Heenan in the lead-up to a match at WrestleMania III, which was promoted as one of the biggest in wrestling history. At the event, Hogan successfully defended the title by body-slamming André, winning the match with a leg drop.[80]

Hogan was named the most requested celebrity of the 1980s for the Make-a-Wish Foundation children's charity. He was featured on the covers of Sports Illustrated (the first and as of 2013, only professional wrestler to do so), TV Guide, and People magazines, while also appearing on The Tonight Show and having his own CBS Saturday morning cartoon titled Hulk Hogan's Rock 'n' Wrestling.[81] He also co-hosted Saturday Night Live on March 30, 1985. AT&T reported that the 900 number information line he ran while with the WWF was the single biggest 900 number from 1991 to 1993.[82] Hogan continued to run a 900 number after joining World Championship Wrestling (WCW).[83]

The Mega Powers (1988–1989)

Hogan lost the WWF title to André the Giant on The Main Event I after a confusing setup involving "The Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase and referee Earl Hebner, who secretly replaced his twin brother, the real referee. After André delivered a belly to belly suplex on Hogan, Hebner counted the pin even though Hogan's shoulder was off the mat. After the match, André gave the title to DiBiase as part of their deal. However, WWF President Jack Tunney ruled that a title couldn't be sold and the championship was vacated.

At WrestleMania IV, Hogan entered a tournament to win the vacant title. He and André both got byes into the quarterfinals, but their match ended in a double disqualification. Later, Hogan helped stop André from interfering in the final match, which allowed Randy Savage to beat DiBiase and win the championship. Afterwards, Hogan, Savage, and manager Miss Elizabeth formed a partnership known as The Mega Powers, feuding with The Mega Bucks and the Twin Towers in the rest of the year.

By the end of 1988, the Mega Powers started a storyline where they begun to fall apart after Savage grew jealous of Hogan and suspected romantic tension between Hogan and Miss Elizabeth. At the 1989 Royal Rumble, Hogan accidentally eliminated Savage while trying to get rid of another wrestler. Soon after at The Main Event II, during a tag match against The Twin Towers Savage accidentally knocked down Elizabeth. Hogan took her backstage for help, leaving Savage alone in the ring. When Hogan returned and asked for a tag, Savage slapped him and walked out. Hogan finished the match and won on his own.

After the match, Savage attacked Hogan backstage, breaking up the partnership and officially starting their feud. This culminated at WrestleMania V, where Hogan defeated Savage to win his second WWF World Heavyweight Championship.

Final WWF Championship reigns and steroid scandal (1989–1993)

.jpg/250px-Hulk_Hogan_vs_Big_Boss_Man_in_March_1989_(cropped).jpg)

During Hogan's second reign as champion, he starred in the film No Holds Barred, which was the inspiration of a feud with Hogan's co-star Tom Lister, Jr., who appeared at wrestling events as his film character Zeus. The duo would fight multiple times across the country during late 1989, including tag team matches at SummerSlam and at the No Holds Barred pay-per-view, with Hogan winning each match. Hogan also defeated Savage to retain the WWF Championship in their official WrestleMania rematch on October 10 at the London Arena.[84][85]

Hogan would to go to win the 1990 Royal Rumble match,[86] during which he encountered the Ultimate Warrior for the first time. Their brief interaction in the match would lead to feud between the pair, culminating in Hogan losing his championship to the Warrior in a title vs title match in the main event of Wrestlemania VI on April 1, 1990.[87]

Afterwards Hogan feuded with Earthquake, who crushed Hogan's ribs in a sneak attack on The Brother Love Show in May 1990. Following this, Hogan teased retirement, and fans were encouraged to send letters asking for his return. Hogan returned by SummerSlam, going on to defeat Earthquake in a series of matches across the country for several months.[88] His defeat of this overwhelmingly large foe prompted Hogan to add a fourth "demandment," believing in yourself, and began calling himself "The Immortal" Hulk Hogan.[citation needed]

In the Royal Rumble in January 1991, Hogan became the first wrestler to win two Royal Rumble matches in a row.[89][4][86][89] At WrestleMania VII, Hogan defeated Sgt. Slaughter for his third WWF Championship, losing the title to The Undertaker at Survivor Series later that year following interference from Ric Flair.[90][91] Jack Tunney immediately granted Hogan a rematch at This Tuesday in Texas six days later, which Hogan won.[92] However, Hogan threw ashes from the Undertaker's urn into his face, resulting in the championship being declared vacant due to the two controversial title changes.[93][91]

It was decided that the winner of the 1992 Royal Rumble match would be declared the new WWF Champion. Hogan entered in the #26 spot, but was eliminated by Sid Justice, who in turn Hogan helped Ric Flair to eliminate, leading to Flair's victory.[94] Hogan was later named the number one contender to face Flair in the main event of WrestleMania VIII. However, while Hogan and Sid briefly teamed up afterward, Sid walked out on Hogan during a tag match at Saturday Night's Main Event XXX, starting a feud.[95] The WrestleMania main event was changed, with Randy Savage facing Flair, while Hogan faced Sid. Hogan defeated Sid via disqualification due to interference by Sid's manager Harvey Wippleman.[96] During this time, news sources began to allege that George Zahorian, a doctor for the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission, had been selling steroids illegally to WWF wrestlers, including Hogan. Amidst public scrutiny, Hogan took a leave of absence from the company in late 1992.[97]

Hogan returned to the WWF in February 1993, helping his friend Brutus Beefcake in his feud with Money Inc.[84] Renaming themselves The Mega-Maniacs, at WrestleMania IX Hogan and Beefcake lost by disqualification to Money Inc. in a match for the WWF Tag Team Championship. Later that night, Hogan won his fifth WWF Championship by pinning Yokozuna in an impromptu match only moments after Yokozuna had defeated Bret Hart for the championship.[98][99] Hogan reportedly used his influence to have the finish of WrestleMania changed the weekend of the event so he would be champion during an upcoming international and de facto farewell tour. WWF Official Bruce Prichard has said in interviews Hogan was made champion to help ticket sales for a WWF tour of Europe.[100]

At the first annual King of the Ring pay-per-view on June 13, Hogan lost the WWF Championship to Yokozuna after Hogan was blinded by a fireball shot by Harvey Wippleman disguised as a "Japanese photographer".[101][102] This was Hogan's last WWF pay-per-view appearance until 2002; after continuing his feud on the international house show circuit with Yokozuna until August 1993, Hogan sat out the rest of his contract which expired later that year.[103]

Before he lost the belt to Yokozuna, on May 3, 1993, Hogan returned to NJPW as WWF Champion and defeated IWGP Heavyweight Champion The Great Muta at Wrestling Dontaku. Hogan also wrestled The Hell Raisers with Muta and Masahiro Chono as his tag team partners. His last match in Japan was on January 4, 1994, at Battlefield, when he defeated Tatsumi Fujinami.[104]

World Championship Wrestling (1994–2000)

World Heavyweight Champion (1994–1996)

Starting in March 1994, Hogan began making appearances on World Championship Wrestling (WCW) television, with interviewer Gene Okerlund visiting him on the set of Thunder in Paradise episodes. On June 11, 1994, Hogan officially signed with WCW in a ceremony that was held at Disney-MGM Studios.[105] He was managed by Jimmy Hart. The next month, Hogan made his in-ring debut at Bash at the Beach defeating Ric Flair to win the WCW World Heavyweight Championship. His arrival was seen as a turning point for the company, bringing mainstream attention, increased pay-per-view sales, and new sponsorships.[106][107]

Afterwards Hogan continued feuding with Flair and later faced other top stars like The Butcher[108] and Vader over the World Championship. He also reunited with Randy Savage, reforming the Mega Powers in WCW.

In September 1995, Hogan headlined the debut episode of WCW Monday Nitro, marking the beginning of the Monday Night Wars with WWF. He began wearing all black and feuded with The Dungeon of Doom, leading to a WarGames match at Fall Brawl where Hogan's team claimed victory.[109] His 469-day title reign, the longest in the title's history, ended at Halloween Havoc after a disqualification loss to The Giant.[110] The title was allowed to change hands under such circumstances due to a previously-agreed contract clause, but the controversy lead to the title being vacated. Hogan was unsuccessful in reclaiming the title at World War III,[111] but would end his feud with The Giant with a cage match victory at SuperBrawl VI.[112] In early 1996, he and Savage formed a team to battle The Alliance to End Hulkamania, defeating them at Uncensored in a Doomsday Cage match.[113]

New World Order and final years in WCW (1996–2000)

At Bash at the Beach 1996, Hulk Hogan turned heel for the first time in nearly fifteen years by attacking Randy Savage and aligning with The Outsiders (Kevin Nash and Scott Hall),[114] cutting a promo afterwards in which he announced the formation of the New World Order (nWo).[114] Rebranding himself as "Hollywood" Hulk Hogan,[2][101] he adopted a new black-and-white persona and dominated WCW, capturing his second WCW World Heavyweight Championship at Hog Wild on August 10 by defeating The Giant for the title.[115] He briefly lost the title to Lex Luger on the August 4, 1997, episode of Nitro, only to regain it five days later at Road Wild.[116] Meanwhile, a lengthy storyline between Sting and the nWo reached its pinnacle at Starrcade on December 28, where Sting defeated Hogan to win the championship in a controversial finish.[117]

A feud with fellow nWo members Kevin Nash and Randy Savage led to the group's split into "nWo Hollywood" led by Hogan and "nWo Wolfpac" led by Nash; Hogan defeated Savage to win his fourth WCW World Heavyweight Championship on the April 20, 1998, episode of Nitro.[118] He lost the title to the then-undefeated Bill Goldberg on the July 6, 1998 episode of Nitro.[119] After this, he spent the rest of 1998 in high-profile celebrity matches at various WCW PPVs, involving the likes of Dennis Rodman, Kevin Malone,[120] and Jay Leno.[121] In late 1998, he announced a presidential run and retirement from wrestling,[122] which were later revealed as publicity stunts derived from Jesse Ventura's recent Minnesota gubernatorial win.[122]

Hogan returned to WCW in January 1999 during the infamous "Fingerpoke of Doom" match, where he reclaimed the WCW title from Kevin Nash via a simple poke to Nash's chest in a staged finish, with the pair afterwards reunifying the nWo factions.[123][124] The incident is widely seen as a key factor in WCW’s decline in ratings and popularity.[125] Later that year in March, he lost the title to Ric Flair at Uncensored[2][126] and returned as a babyface in July, defeating Savage to win his sixth and final WCW World Heavyweight Championship on the July 12 episode of Nitro.[127] Hogan dropped the title to Sting.[128] in September 1999. In the rematch at Halloween Havoc, Hogan came to the ring in street clothes, laid down for the pin, and left the ring.[129] Hogan was convinced shortly after by head booker Vince Russo to take time off .[130]

At Bash at the Beach on July 9, 2000, Hogan was involved in a controversial segment. Hogan was scheduled to challenge Jeff Jarrett for the WCW World Heavyweight Championship,[131] however before the match, there was a backstage dispute between Hogan and Russo. The match ending was changed to a worked shoot where Jarrett laid down for Hogan, with Hogan after winning disparaging Russo and the company on the microphone. Moments later, Russo came to the ring and said this would be "the last time fans would ever see that piece of shit in a WCW ring" whilst revealing Hogan's creative control clause in his contract.[101]

As a result, Hogan filed a defamation of character lawsuit against Russo,[132] which was eventually dismissed in 2002. It is not clear how legimate everything that transpired in the ring was legimate; Russo claims the entire incident was a work, and Hogan claimed that Russo had turned it into a shoot when Russo went into the ring.[133] Eric Bischoff agreed with Hogan's side of the story when he wrote that Hogan winning and leaving with the belt was a work, and that he and Hogan celebrated after the event over the success of the angle, but that Russo coming out to fire Hogan was unplanned. Regardless, the incident marked Hogan's final apperance in WCW.[2][132]

In the months afterwards, in March 2001 Hogan underwent surgery on his knees, wrestling in a match for Xcitement Wrestling Federation (XWF) in November 2001 in preperation for his return to the WWF in February 2002.[2]

Second return to WWF/WWE (2002–2003)

At No Way Out on February 17, 2002, Hogan returned to the WWF as a heel.[4] Returning as leader of the original nWo with Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, the three got into a confrontation with The Rock[134] and cost Stone Cold Steve Austin a chance at becoming the Undisputed WWF Champion against Chris Jericho in the main event.[134] The nWo feuded with both Austin and The Rock, and on the February 18 episode of Raw, Hogan accepted The Rock's challenge to a match at WrestleMania X8 on March 17,[135] where Hogan asked Hall and Nash not to interfere, wanting to defeat The Rock by himself. Despite the fact that Hogan was supposed to be the heel in the match, the crowd cheered for him heavily. The Rock cleanly won the contest,[136] and befriended Hogan at the end of the bout, helping him fight off Hall and Nash, who were upset by Hogan's conciliatory attitude.[137] After the match, Hogan turned face by siding with The Rock, though he continued wearing black and white tights for a few weeks after WrestleMania X8 until he resumed wearing his signature red and yellow tights. During this period, the "Hulk Rules" logo of the 1980s was redone with the text "Hulk Still Rules", and Hogan also wore the original "Hulk Rules" attire twelve years earlier, when he headlined WrestleMania VI at the same arena, in the SkyDome. For a time, he was still known as "Hollywood" Hulk Hogan, notably keeping the Hollywood Hogan style blond mustache with black beard while wearing Hulkamania-like red and yellow tights and using the "Voodoo Child" entrance theme music he'd used in WCW. On the March 25 episode of Raw, Hogan was drafted to the SmackDown! brand as part of the inaugural draft lottery.[138] On the April 4 episode of SmackDown!, Hogan began a feud with Triple H,[139] and then defeated Triple H for the Undisputed WWF Championship at Backlash on April 21.[140][141] Two weeks later, WWF changed its name to WWE, hence Hogan was the final "WWF Champion" and the first "WWE Champion".[142]

On May 19 at Judgment Day, Hogan lost the WWE Undisputed Championship to The Undertaker.[143] After losing a number one contender match for the WWE Undisputed Championship to Triple H on the June 6 episode of SmackDown!,[144] Hogan began feuding with Kurt Angle resulting in a match between the two at the King of the Ring on June 23, which Angle won by submission.[145] Hogan also had a 19 days reign as WWE Tag Team Champion with Edge.[146][147] In August, Hogan was used in an angle with Brock Lesnar, culminating in a main event singles match on the August 8 episode of SmackDown!, which Lesnar won by technical submission. Lesnar became only the second WWE wrestler to defeat Hogan by submission (after Kurt Angle).[148]

Hogan went on hiatus until early 2003, shaving off his black beard and dropping "Hollywood" from his name in his return.[149] Hogan battled The Rock (who had turned heel) once again at No Way Out on February 23 and lost[150] and defeated Mr. McMahon at WrestleMania XIX on March 30 in a street fight billed as "twenty years in the making".[151] Hogan's next storyline had McMahon forcing Hogan to sit out the rest of his contract, leading to him debuting the masked Mr. America character.[2] On the May 1 episode of SmackDown!, Mr. America debuted on a Piper's Pit segment. McMahon appeared and claimed that Mr. America was Hogan in disguise; Mr. America shot back by saying, "I am not Hulk Hogan, brother!".[2] The feud continued through May, with a singles match between Mr. America and Hogan's old rival "Rowdy" Roddy Piper at Judgment Day on May 18, a match Mr. America won.[152]

Mr. America's last WWE appearance was on the June 26 episode of SmackDown! when Big Show and The World's Greatest Tag Team (Charlie Haas and Shelton Benjamin) defeated Brock Lesnar, Kurt Angle, and Mr. America in a six-man tag team match.[153] After SmackDown! went off the air, Mr. America unmasked to show the fans that he was indeed Hogan, putting his finger to his lips telling the fans to keep quiet about his secret. The next week, Hogan quit WWE due to frustration with the creative team.[154] On the July 3 episode of SmackDown!, McMahon showed the footage of Mr. America unmasking as Hogan and "fired" him, although Hogan had already quit in real life.[154] It was later revealed that Hogan was unhappy with the payoffs for his matches after his comeback under the Mr. America gimmick.[154]

Second return to NJPW (2003)

Hogan returned to NJPW in October 2003, when he defeated Masahiro Chono at Ultimate Crush II in the Tokyo Dome. Shortly after Hogan left WWE, Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA) began making overtures to Hogan, culminating in Jeff Jarrett, co-founder of TNA and then NWA World Heavyweight Champion, launching an on-air attack on Hogan in Japan after the Chono match. The attack was supposed to be a precursor to Hogan battling Jarrett for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship at TNA's first three-hour pay-per-view. Due to recurring knee and hip problems, Hogan did not appear in TNA.[155]

Third return to WWE (2005–2007)

On April 2, 2005, Hogan was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame class of 2005 by actor and friend Sylvester Stallone.[156] At WrestleMania 21 on April 3, Hogan came out to rescue Eugene, who was being attacked by Muhammad Hassan and Khosrow Daivari.[157] The build-up to Hogan's Hall of Fame induction and preparation for his WrestleMania angle was shown on the first season of Hogan Knows Best. The next night on Raw, Hassan and Daivari came out to confront and assault fan favorite Shawn Michaels.[158] At Backlash on May 1, Hassan and Daivari lost to Hogan and Michaels.[159]

Hogan then appeared on July 4 episode of Raw, as the special guest of Carlito on his talk-show segment Carlito's Cabana. After being asked questions by Carlito concerning his daughter Brooke, Hogan attacked Carlito. Kurt Angle then also appeared, making comments about Brooke, which further upset Hogan, who was eventually double teamed by Carlito and Angle, but was saved by Shawn Michaels. Later that night, Michaels and Hogan defeated Carlito and Angle in a tag team match; during the post-match celebration, Michaels performed the Sweet Chin Music on Hogan and walked off.[160] The following week on Raw, Michaels appeared on Piper's Pit and challenged Hogan to face him one-on-one for the first time.[161] Hogan appeared on Raw one week later and accepted the challenge.[162] The match took place at SummerSlam on August 21, which Hogan won. After the match, Michaels extended his hand to him, telling him that he "had to find out for himself", and Hogan and Michaels shook hands as Michaels left the ring to allow Hogan to celebrate with the crowd.[163]

Prior to WrestleMania 22 in April 2006, Hogan inducted friend and former announcer "Mean" Gene Okerlund into the WWE Hall of Fame class of 2006. Hogan returned on Saturday Night's Main Event XXXIII with his daughter Brooke. During the show, Randy Orton flirted with Brooke and later attacked Hogan in the parking lot.[164] He later challenged Hogan to a match at SummerSlam on August 20, which Hogan won, finishing with a perfect 6-0 record at SummerSlam.[165] This was Hulk Hogan's final match wrestling for the WWE, although he had negotiations for a match against John Cena at WrestleMania 25 which ultimately fell through.[166][167]

Independent circuit (2007, 2009)

During this time Hogan was invited to join Memphis Wrestling to face Jerry Lawler.[168] Although the match had been promoted for months, contractual obligations prevented Lawler from participating, and he was replaced by Paul Wight.[168] Hogan defeated Wight at the PMG Clash of Legends event on April 27, 2007.[169]

Throughout November 2009, Hogan performed in an independent wrestling tour across Australia titled Hulkamania: Let The Battle Begin. The main event of each show was a rematch between Hogan and Ric Flair, with Hogan winning each match.[170][171]

Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (2009–2013)

On October 27, 2009, it was announced that Hogan had signed with Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA).[172] Hogan debuted on the January 4, 2010, episode of Impact! alongside Eric Bischoff in an executive role.[173] Over the next few weeks, Hogan began an on-screen mentorship with Abyss,[174] and the two teamed to defeat A.J. Styles and Ric Flair in Hogan's first TNA match on the March 8 episode of Impact!.[175] At Lockdown on April 18, Team Hogan (Hogan, Abyss, Jeff Jarrett, Jeff Hardy and Rob Van Dam) defeated Team Flair (Flair, Sting, Desmond Wolfe, Robert Roode and James Storm) in a Lethal Lockdown match.[176]

After months of storylines involving speculation about a secretive controlling force in TNA,[177][178] Hogan turned heel by helping Hardy win the TNA World Heavyweight Championship at Bound for Glory on October 10, 2010, forming Immortal with Hardy, Bischoff, Abyss and Jarrett.[179] As part of the angle, it was revealed that Bischoff had tricked TNA President Dixie Carter into signing paperwork to turn the company over to him and Hogan.[180] The storyline concluded at Bound for Glory on October 16, 2011, when Hogan lost to Sting in a match that returned control of TNA to Carter. After the match, Hogan aided Sting during a post-match attack by members of Immortal, marking his return to a fan favorite role.[181]

Hogan wrestled his final matches during TNA's tour of the United Kingdom, on January 26 and 27, 2012, at house shows in Nottingham and Manchester, where he, James Storm and Sting defeated Bobby Roode, Bully Ray and Kurt Angle in a six-man tag team main event at both events.[182][183] Two months later, Hogan assumed the role of TNA's on-screen General Manager.[184] His last major storyline in TNA was with the mysterious masked group Aces & Eights;[185] the storyline included an angle where Bully Ray was in a relationship with his daughter Brooke,[186][187] culminating at Lockdown on March 10, 2013, where Ray was revealed to be the leader of Aces & Eights.[188] Hogan left TNA in October 2013 upon the expiration of his contract. His final appearance was on the October 3 episode of Impact Wrestling.[189]

Fourth return to WWE (2014–2015)

.jpg/250px-WWE_Raw_IMG_5754_(13772931635).jpg)

On February 24, 2014, on Raw, Hogan made his first WWE in-ring appearance since December 2007 to hype the WWE Network.[190] On the March 24 episode of Raw, Hogan came out to introduce the guest appearances of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Joe Manganiello; this was to promote the guests' new film Sabotage.[191]

At WrestleMania XXX in April 2014, Hogan served as the host, coming out at the start of the show to hype up the crowd. During his promo, he mistakenly referred to the Superdome, the venue the event was being held at, as the Silverdome, which became the subject of jokes throughout the night.[192] Hogan was later joined by Stone Cold Steve Austin and The Rock, and they finished their promo by drinking beer together in the ring.[193] Later in the show, Hogan shared a moment with Mr. T, Paul Orndorff and Roddy Piper, in a reference to the first WrestleMania.[194]

On February 27, 2015, Hogan was honored at Madison Square Garden during a WWE live event dubbed "Hulk Hogan Appreciation Night" with a special commemorative banner hanging from the rafters, honoring his wrestling career and historic matches he had in the arena.[195] Hogan then appeared on the March 23 episode of Raw, where he and Snoop Dogg got the better of Curtis Axel, who was promoting "AxelMania".[196] On March 28, Hogan posthumously inducted "Macho Man" Randy Savage into the WWE Hall of Fame class of 2015.[197] The next night at WrestleMania 31, Hogan, Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, representing the nWo, interfered in the Sting–Triple H match on behalf of Sting, where they battled D-Generation X (DX) members Billy Gunn, X-Pac, Road Dogg, and Shawn Michaels.[198]

Racism scandal and departure

In July 2015, National Enquirer and Radar Online publicized an anti-black rant made by Hogan on a leaked sex tape recorded in 2007. In the recording, he is heard expressing disgust with the notion of his daughter dating a black man, referenced by repeated use of the racial slur "nigger".[199][200] Hogan also said that he was "a racist, to a point".[200] Once the recordings went public erupting in a media scandal, Hogan apologized for the remarks, which he said is "language that is offensive and inconsistent with [his] own beliefs".[201] Radar Online later reported that Hogan had also used homophobic slurs on the leaked sex tape.[202] It was also reported that Hogan had used racist language in a 2008 call to his then-imprisoned son, Nick, and also said that he hoped they would not be reincarnated as black males.[203]

On July 24, WWE terminated their contract with Hogan;[204] however, Hogan's lawyer said Hogan chose to resign.[201] In response to the scandal, WWE removed almost all references to Hogan from their website, including his entry from its WWE Hall of Fame page and his merchandise from WWE Shop. Hogan’s characters were removed from WWE video games,[205][206] Mattel halted production of his action figures, and retailers including Target, Toys "R" Us, and Walmart pulled his merchandise from their online stores.[207]

Hogan gave an interview with Good Morning America on August 31 in which he pleaded forgiveness for his racist comments, attributing these to a racial bias inherited from his neighborhood while growing up.[208] Hogan said that the term "nigger" was used liberally among friends in Tampa; former neighbors disputed this.[209]

Reaction from African-American wrestlers

The scandal spurred a range of responses from across the professional wrestling industry. Hogan received some support from his African-American peers. Virgil,[210] Dennis Rodman[211] and Kamala each spoke positively about their experiences with Hogan and did not believe he was racist.[212] Other black wrestlers working in the WWE made more critical comments, including Mark Henry, who said he was pleased by WWE's "no tolerance approach to racism" response and that he was hurt and offended by Hogan's manner and tone.[213] Booker T said he was shocked and called the statements unfortunate.[214] In the time that followed, numerous African-Americans associated with wrestling expressed some level of support for Hogan including: Rodman,[215] The Rock,[216] Booker T[217] Kamala,[218] Virgil,[219] Mr. T,[220] Henry,[221] and Big E.[222]

Upon his return to the company in 2018, Hogan talked to all the wrestlers backstage to apologize.[223] Several African-American wrestlers, including The New Day, Titus O'Neil, Mark Henry, Shelton Benjamin and JTG doubted the sincerity of Hogan's apology,[224][225][226][227][228][229] due to Hogan warning wrestlers to be "mindful about being recorded without their knowledge" during his apology instead of addressing his comments.[223][230][231]

Fifth return to WWE (2018–2025)

On July 15, 2018, Hogan was "reinstated" into the WWE Hall of Fame[232] (despite no prior official statement suspending him). Hogan made his on-screen return on November 2, 2018, as the host of Crown Jewel.[233] On January 7, 2019, Hogan returned to Raw to present a tribute to Gene Okerlund, who had died five days prior.[234]

During the following years, Hogan appeared on several WWE events, like the 2019 and 2020 Hall of Fame ceremonies, where he inducted Brutus Beefcake in 2019 and was inducted for a second time as part of the New World Order (with Scott Hall, Kevin Nash and Sean Waltman) in 2020.[235][236] He also hosted the 35 and 37 editions of WrestleMania, along with Alexa Bliss and Titus O'Neil respectively.[237][238][239] He also participated at Crown Jewel 2019, where he was the captain of a team opposing Ric Flair's team.[240]

In January 2025, Hogan made his final appearance at a professional wrestling event during the Raw debut on Netflix, where alongside Jimmy Hart he cut a promo advertising his Real American Beer. Hogan was heavily booed by the crowd, which received widespread coverage in the media.[241]

Endorsements and business ventures

Food, beverage, restaurants and wrestling shops

Hogan created and financed a restaurant called Pastamania located in the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota.[242] It opened on the Labor Day weekend of 1995 and was heavily promoted on WCW's live show Monday Nitro. The restaurant, which remained in operation for less than a year, featured such dishes as Hulk-U's and Hulk-A-Roos.[242]

In interviews on The Tonight Show and Late Night with Conan O'Brien, Hogan claimed that the opportunity to endorse what came to be known as the George Foreman Grill was originally offered to him, but when he failed to respond in time, Foreman endorsed the grill instead. However, there is no evidence to support this claim.[243][244] Instead, Hogan endorsed a blender, known as the Hulk Hogan Thunder Mixer. He later endorsed a grill known as The Hulk Hogan Ultimate Grill, voluntarily recalled as a fire hazard in 2008 along with other QVC and Tristar grills.[245]

In 2006, Hogan unveiled Hogan Energy, a drink distributed by Socko Energy.[246] His name and likeness were also applied to a line of microwavable hamburgers, cheeseburgers, and chicken sandwiches sold at Wal-Mart called Hulkster Burgers.[247] On November 1, 2011, Hogan launched a website called Hogan Nutrition featuring many nutritional and dietary products.[248]

On New Year's Eve 2012, Hogan opened a beachfront restaurant called Hogan's Beach near Tampa, Florida.[249][250] The restaurant dropped Hogan's name in October 2015.[251] Hogan later opened Hogan's Hangout in Clearwater Beach, within walking distance from his memorabilia store. Hogan regularly would host Karaoke tournaments that featured Ric Flair and Jimmy Hart; and where hosted by his son Nick Hogan on Monday Nights called "Main Event Karaoke". [252]

In 2017, Hogan opened a second memorabilia store on International Drive in Orlando, Fl during Wrestlemania 34 weekend. In 2024, the memorabilia stores names changed from Hulk Hogan’s Beach Shop to Hulk Hogan’s Wrestling Shop. In May 2024, Hogan announced the opening of a second bar across from Madison Square Garden in New York City. A third memorabilia store opened in 2025 shortly before his death in Pigeon Gorge Tennessee.

In 2024, Hogan launched Real American Beer, a light beer brand.[253][254]

Politics

Hogan endorsed Donald Trump for president at the 2024 Republican National Convention.[255] He notably spoke at the 2024 Trump rally at Madison Square Garden.[256]

Other

In October 2007, Hogan transferred all trademarks referring to himself to his liability company named Hogan Holdings Limited. The trademarks include Hulk Hogan, "Hollywood" Hulk Hogan, Hulkster, Hogan Knows Grillin, Hulkamania.com, and Hulkapedia.com.[257]

In April 2008, Hogan announced that he would license Gameloft to create a Hulkamania Wrestling video game for mobile phones. He stated in a press release that the game would be "true to [his] experiences in wrestling" and use his classic wrestling moves like the Doublehand Choke Lift and Strong Clothesline.[258] In 2010, Hogan starred alongside Troy Aikman in commercials for Rent-A-Center.[259] On March 24, 2011, Hogan made a special appearance on American Idol, surprising Paul McDonald and James Durbin, who were both wrestling fans. On October 15, 2010, Endemol Games UK (a subsidiary of media production group Endemol UK) announced a partnership with Bischoff Hervey Entertainment to produce Hulk Hogan's Hulkamania, an online gambling game featuring video footage of Hogan.[260][261]

In October 2013, Hogan partnered with Tech Assets, Inc. to open a web hosting service called Hostamania.[262] A commercial video promoting the service featured Hogan parodying Jean-Claude Van Damme's GoDaddy.com commercials and Miley Cyrus' "Wrecking Ball" music video.[263][264] On November 21, 2013, Hulk Hogan and GoDaddy.com appeared together on a live Hangout On Air on Google Plus.[265]

Hogan became a distributor for multi-level marketing company ViSalus Sciences after looking for business opportunities outside of wrestling.[266] Hogan supported the American Diabetes Association.[267]

In 2019, it was announced that Chris Hemsworth would portray Hogan in a biopic, directed by Todd Phillips.[268] However, plans for the film had been scrapped by 2024.[269]

In 2025, he appeared in the documentary film Wrestlemania IX: The Spectacle. The documentary was released on Peacock on April 11, 2025.[270][271][272]

Hogan co-founded Real American Freestyle in April 2025, and he served as the promotion's commissioner.[273]

Other media

Acting

.jpg/250px-Hulk_Hogan%27s_handprints_in_cement_(Great_Movie_Ride%2C_Walt_Disney_World%27s_Disney%27s_Hollywood_Studios).jpg)

Hogan's crossover popularity led to several television and film roles. Early in his career Hogan played the part of Thunderlips in Rocky III (1982). He also appeared in No Holds Barred (1989), before starring in family films Suburban Commando (1991), Mr. Nanny (1993), Santa with Muscles (1996), and 3 Ninjas: High Noon at Mega Mountain (1998).[274] Hogan also appeared in 1992 commercials for Right Guard deodorant. He starred in his own television series, Thunder in Paradise, in 1994. He is the star of The Ultimate Weapon (1998), in which Brutus Beefcake also appears in a cameo.[275]

In 1997, Hogan starred in the TNT original film Assault on Devil's Island, as the leader of a commando unit featuring fellow genre veterans Carl Weathers and Shannon Tweed. Eric Bischoff was also listed as an executive producer. The characters were considered for a regular series, but instead received a second feature-length showcase two years later, called Assault on Death Mountain. In 1995, he appeared on TBN's Kids Against Crime. Hogan made cameo appearances in Muppets from Space, Gremlins 2: The New Batch (the theatrical cut) and Spy Hard as himself. Hogan also played the role of Zeus in Little Hercules in 3D. Hogan also made two appearances on The A-Team (in 1985 and 1986), along with Roddy Piper. He also appeared on Suddenly Susan in 1999.[276]

Hogan voiced "The Dean" in the 2011 animated show China, IL.[277][278]

Reality television and hosting

On July 10, 2005, VH1 premiered Hogan Knows Best a reality show which centered around Hogan, his then-wife Linda, and their children Brooke and Nick.[279] In July 2008, a spin-off entitled Brooke Knows Best premiered, which focused primarily on Hogan's daughter Brooke.[280]

Hogan hosted the comeback series of American Gladiators on NBC in 2008.[281] He also hosted and judged the short-lived reality show, Hulk Hogan's Celebrity Championship Wrestling.[282] Hogan had a special titled Finding Hulk Hogan on A&E on November 17, 2010.[283]

In 2015, Hogan was a judge on the sixth season of Tough Enough, alongside Paige and Daniel Bryan,[284] but due to that year's Hogan scandal, he was replaced by The Miz.[285]

Music and radio

Hogan released a music CD, Hulk Rules, as Hulk Hogan and the Wrestling Boot Band, which also included Jimmy "Mouth of the South" Hart, his then-wife Linda and J.J Maguire.[286] Despite negative reviews, Hulk Rules reached No. 12 on the Billboard Top Kid Audio chart in 1995.[286] Hogan and Green Jellÿ in 1993 performed a cover version of Gary Glitter's song "I'm the Leader of the Gang (I Am)".[287] In the 1980s, Hogan appeared in the music video for Dolly Parton's wrestling-themed love song "Headlock on My Heart" for Parton's show Dolly.[287]

Hogan was a regular guest on Bubba the Love Sponge's radio show. He also served as the best man at Bubba's January 2007 wedding.[288] On March 12, 2010, Hogan hosted his own radio show titled Hogan Uncensored, on Sirius Satellite Radio's Howard 101.[289]

Merchandising

The Wrestling Figure Checklist records Hogan as having 171 different action figures, produced between the 1980s and 2010s from numerous manufacturers and promotions.[290]

Video games

Hogan provided his voice for the 2011 game Saints Row: The Third as Angel de la Muerte, a member of the Saints.[291] In October 2011, he released a video game called Hulk Hogan's Main Event.[292]

Personal life

Legal issues

Belzer lawsuit

On March 27, 1985, Richard Belzer requested on his cable TV talk show Hot Properties that Hogan demonstrate one of his signature wrestling moves. Hogan put Belzer in a modified guillotine choke, which caused Belzer to pass out. When Hogan released him, Belzer hit his head on the floor, sustaining a laceration to the scalp that required a brief hospitalization. Belzer sued Hogan for $5 million and later settled out of court. On the October 20, 2006, broadcast of the Bubba the Love Sponge Show, it was claimed (with Hogan in the studio) that the settlement totaled $5 million, half from Hogan and half from Vince McMahon. However, Belzer suggested that the settlement amount was closer to $400,000.[293]

Testimony in McMahon trial

In 1991, on The Arsenio Hall Show, Hogan denied using steroids, stating "I trained 20 years two hours a day to look like I do. But the things that I'm not, I am not a steroid abuser and I do not use steroids."[294][295] Billy Graham, a fellow wrestler, in a 1991 interview on Inside Edition, stated that he injected Hogan with steroids in the 80's.[296] In 1993, media reports indicated that Hogan was a heavy steroid user.[297]

In 1994, Hogan, having received legal immunity, testified in the trial of Vince McMahon relating to shipments of steroids received by both parties from WWF physician George T. Zahorian III.[298] Under oath, Hogan admitted that he had used anabolic steroids since 1976 to gain size and weight, but that McMahon had neither sold him the drugs nor ordered him to take them. The evidence given by Hogan proved extremely costly to the government's case against McMahon. Due to this and jurisdictional issues, McMahon was found not guilty.[299]

During his testimony, Hogan said that he and King Kong Bundy had gone to McMahon to tip him off over Jesse Ventura's unionization efforts in 1986.[300][301][302] Hogan later stated "Vince already knew about it, I just said I didn't think it was a good idea. [Ventura] was running his mouth like usual, trying to get everyone on board, everyone knew".[130] This led to criticism; no professional wrestlers' union has been established.[303][304][305]

Sexual assault allegation and extortion lawsuit

In January 1996, Hogan was accused of sexual assault by a 29-year-old businesswoman on Labor Day weekend in 1995.[306][307] The incident is alleged to have occurred at the first WCW Nitro taping at the Mall of America in Minneapolis. The woman claims she was helping Hogan to sell merchandise for his Pastamania restaurant and when she went to deliver the leftover merchandise to him at his hotel room after the show, Hogan forced her to perform oral sex on him.[308] She also claimed to have evidence that Hogan raped another woman.[309] The woman and her lawyer sent Hogan a letter agreeing to settle the case financially before making it public, and Hogan sued for extortion.[310][307] Gene Okerlund claimed he was with Hogan the whole day and denied the allegations.[306] The woman filed a counter-suit against Hogan in 1997.[308]

Gawker lawsuit

In 2012, Gawker released a short clip of a sex tape between Hogan and Heather Clem, the estranged wife of radio personality Bubba the Love Sponge.[311] Hogan stated that the tape was made without his knowledge or consent,[312] and he sued Bubba and Heather Clem for invading his privacy on October 15, 2012.[313] A settlement with Bubba was announced later that month,[314] who subsequently issued a public apology.[315] In lawsuit financed by Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel,[316] Hogan also sued Gawker for $100 million for defamation, loss of privacy, and emotional pain.[317] After a 2016 trial, Hogan was awarded $115 million.[318][319] Also, on August 11, 2016, a Florida judge gave Hogan control of the assets of A. J. Daulerio, former Gawker editor-in-chief, who was involved in the posting of Hogan's sex tape.[320] Gawker ultimately reached a $31 million settlement with Hogan in November 2016.[321]

Alleged fabrications

Hogan was accused multiple times of fabricating elements of his past. The Independent said "a great believer in self-mythologising, Hogan was known for stretching the truth about his already remarkable life – often to outrageous extremes."[322] Some of Hogan's statements include claiming that Elvis Presley was a big fan of his (Presley died only a few days after Hogan had his first match),[322] that the "difference in time zones" flying between the US and Japan caused him to wrestle "400 days in a single year",[322] that his neck was severely injured by the Undertaker dropping him on his head performing his signature Tombstone piledriver move at Survivor Series in 1991 (when Undertaker saw the tape of the match he saw that he safely performed the move with Hogan's head a foot away from making contact with the mat, and when confronting Hogan, Hogan claimed it was due to whiplash while taking the move),[323] that both the Rolling Stones and Metallica wanted him to play bass guitar for their bands (Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich denied having ever met Hogan),[324][322][325] and that he was offered the starring role in the film The Wrestler (2008) but turned it down (Director Darren Aronofsky said the role was written for star Mickey Rourke and he never considered Hogan).[326] During an appearance on Bubba the Love Sponge, Hogan claimed to have a 10-inch (25 cm) penis. During the Gawker trial, he admitted in court that this was not true, claiming he was speaking as the character Hulk Hogan, and not as Terry Bollea.[327]

Family

In 1983, Hogan married his first wife, Linda Claridge. They had two children: a daughter, Brooke, and a son, Nick.[328] On November 20, 2007, Linda filed for divorce,[329] stating publicly that she decided to end her marriage after discovering that Hogan had an affair.[330][331] Hogan denied ever cheating on Linda,[332] and stated if he could change one thing in his life it would be to "get divorced right after Nick was born".[130] In the divorce settlement, Hogan retained around 30% of the couple's liquid assets, totaling around $10 million.[333] Hogan said he contemplated suicide after the divorce and credited American Gladiators co-star Laila Ali with preventing it.[334]

Hogan began a relationship with Jennifer McDaniel in early 2008.[335] The two were engaged in November 2009[335] and married on December 14, 2010, in Clearwater, Florida.[336][337] The couple divorced in 2021.[338]

Hogan became engaged to yoga instructor Sky Daily in July 2023, proposing to her at actor Corin Nemec's wedding reception.[339][340] They married on September 22, 2023.[341]

Through Brooke, Hogan would have two grandchildren who were born in January 2025. However, he would not meet them by the time of his death in July 2025.[342]

Religious beliefs

Hogan was public about his Christian faith, stating that he was "saved" at the age of 14 and had "leaned on" his religion throughout his life.[343] He and his wife, Sky Daily, were baptized at Indian Rocks Baptist Church in Largo, Florida on December 20, 2023.[344][345]

Health problems

Hogan suffered numerous health problems, particularly with his back, since retiring as a wrestler following years of heavy weight-training and jolting as a wrestler.[346] He underwent at least 25 medical procedures, including back surgeries, and knee and hip replacements.[347]

After the procedures failed to cure his back problems, Hogan underwent traditional spinal fusion surgery in December 2010, which enabled him to return to his professional activities. In January 2013, Hogan filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against the Laser Spine Institute for $50 million, saying that the medical firm persuaded him to undergo a half-dozen "unnecessary and ineffective" spinal operations that worsened his back problems.[348][349] He claimed that the six procedures he underwent over a period of 19 months only gave him short-term relief.[350] In addition, the Laser Spine Institute used his name on their advertisements, which Hogan claimed was without his permission.[351] The Laser Spine Institute shut down in 2019.[352]

In July 2025, Brooke Hogan stated that Hogan's health was declining by 2023, and that he had undergone numerous surgeries by this point in time.[353]

Death

On May 14, 2025, Hogan underwent a four-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion procedure.[347] Close friends Jimmy Hart and Eric Bischoff noted a rapid decline in Hogan's health following his neck fusion surgery. Hart shared that Hogan avoided visitors to prevent infection,[354] while Bischoff recalled Hogan sounding weak and expressing embarrassment over his condition.[355] On June 18, 2025, radio host Bubba the Love Sponge reported that Hogan was seriously ill in hospital and "might not make it".[347]

Hogan died at his Clearwater, Florida, home on the morning of July 24, 2025, at the age of 71.[356] He collapsed while doing therapy after returning home from hospital,[347] and was taken by paramedics to Morton Plant Hospital, where he was pronounced dead.[357] His official cause of death was acute myocardial infarction, known as a heart attack.[358] His medical records later revealed he had been battling chronic lymphocytic leukemia and atrial fibrillation.[359][360]

On August 5, 2025, Hogan's first funeral service was held at Indian Rocks Baptist Church in Largo, Florida with widow Sky Daily, ex-wife Linda Hogan, Vince McMahon, Triple H, Stephanie McMahon, Ric Flair, Dennis Rodman, singer Kid Rock, Theo Von, and skateboarder Bam Margera being among those in attendance.[361][362][363][364] Daughter Brooke, who was estranged from her father since 2023, did not attend his funeral services.[365][366] Following another funeral service which was held at Sylvan Abbey Memorial Park & Funeral Home in Clearwater, Florida, Hogan was cremated and laid to rest.[365][362][367]

Tributes and legacy

Hogan has been described as one of the largest attractions in professional wrestling history and a major reason why Vince McMahon's expansion of his promotion worked. Wrestling historian and journalist Dave Meltzer stated that "...You can't possibly overrate his significance in the history of the business. And he sold more tickets to wrestling shows than any man who ever lived".[368] Hogan himself had previously said he is the second-greatest wrestler ever, after Ric Flair,[369] although Chris Jericho has stated that Hogan is a better worker than Flair and that working with him was one of the favorite moments of Jericho’s career.[370] Meanwhile, Cody Rhodes has said numerous times that Hogan's WrestleMania X8 match with The Rock is the greatest match in wrestling history and that it epitomized what professional wrestling is.[371][372] Bret Hart has issued both praise and criticism for Hogan, lauding his look and describing him as a "hero" to both fans and fellow wrestlers, but calling his in-ring abilities "very limited."[373][374][375]

Following Hogan's death on July 24, 2025, many wrestlers paid tribute to Hogan on social media, such as The Rock, The Undertaker, John Cena, Triple H, Ric Flair, Kane, Sting, Kurt Angle, The Miz and Matt Hardy.[376][377][378] Promotions like WWE, TNA, NWA, NJPW and AEW also remembered him.[379][380][381] Hogan was also remembered by people outside pro wrestling, like actor Sylvester Stallone, UFC President Dana White and U.S. President Donald Trump.[382][383]

WWE honored Hogan with multiple tributes: first on the July 25 episode of SmackDown,[384] then on the following episodes of Raw and NXT,[385][386][387] and also at SummerSlam.[388] Meanwhile, TNA dedicated its July 24 episode of Impact! to Hogan.[389] In NJPW, Hogan was given a ten-bell salute, as well as a tribute ceremony, during the sixth night of the G1 Climax 35 tournament on July 26.[390][391] Two days later, Hogan was honored on AEW Collision with a tribute from former WCW commentator Tony Schiavone.[392]

On July 31, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis declared August 1 as Hulk Hogan Day for the state, in Hogan's memory. DeSantis also declared for the flags at the Florida State Capitol to be flown at half-staff on August 1.[393]

At the same time, many sources noted his complicated legacy due to his backstage politics, his racial comments, and his support for Donald Trump.[394][395][396][322]

Championships and accomplishments

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Jones, Patrick (2002). "Hulk Hogan". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Hulk Hogan's profile". Online World of Wrestling. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (May 28, 2018). "Hulk Hogan trying to bodyslam "Hulk" cereal ad". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Hulk Hogan bio". WWE. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Mike (January 1, 2021). "Why WSX Died A Quick Death On MTV, High Energy, Punk In 2021 And More". PWInsider. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Wrestling Classics, January 1992 issue, p. 16.

- ^ Judgment Day 2003 (DVD). WWE Home Video. 2003.

- ^ "Amended Complaint" (PDF). documentcloud.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Bollea v. Gawker Media, LLC, Case No. 8:12-cv-02348-T-27TBM | Casetext Search + Citator". Archived from the original on January 8, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "Top 10 Wrestling Moustaches of All Time - PROGRESS Wrestling". progresswrestling.com. November 17, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ "Top 50 Wrestlers of All Time – Page 5". IGN. November 2, 2012. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

Hogan is the most recognized wrestling star worldwide and the most popular wrestler of the '80s.

- ^ Assael, Shaun (2002). Sex, Lies, and Headlocks: The Real Story of Vince McMahon and the WWF. Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0609607042.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ "Hulk Hogan's career timeline". ESPN. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ Murray, Jim (September 24, 1991). "Wrestling With His Indentity". LA Times. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Melok, Bobby (November 8, 2012). "Kaitlyn's top 10 Superstar mustaches". WWE. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ Gunier, Robert (December 21, 2022). "Why Antonio Inoki's WWE Championship Reign Isn't Recognized By The Promotion". Wrestling Inc. Retrieved July 28, 2025.

- ^ Keller, Wade. "List of longest WWE title reigns". ProWrestling.net. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ Hornbaker, Tim (2018). Death of the Territories. ECW Press. ISBN 9781773052328.

- ^ Shoemaker, David (March 29, 2017). "The 30 Greatest Pro Wrestlers of All Time". The Ringer. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "WWE to honor nWo with Hall of Fame induction". ESPN. December 9, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "Billboard Top Kid Albums, Sept 1995". Billboard. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ Riddle, Safiyah (July 25, 2025). "Hulk Hogan's death resurfaces painful contradictions for Black wrestling fans". AP News. Retrieved July 27, 2025.

- ^ Hulk Hogan: This Past Weekend w/ Theo Von #455, July 25, 2023, archived from the original on August 23, 2023, retrieved August 23, 2023

- ^ Serena, Alberto (December 20, 2022). "Hulk Hogan, salde radici piemontesi per la star mondiale del wrestling" [Hulk Hogan, the strong Piedmontese roots of the global star of wrestling]. La Sentinella (in Italian). Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ Paul, Christopher (July 28, 2023). ""Rare Occasion Sees Hulk Hogan Reflect on the Dark Tormenting Past of His Brother's Family"". Essentially Sports. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Kennedy Wynne, Sharon. "Hulk Hogan begs for forgiveness, blames South Tampa 'culture' for racist rant (w/video)". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ a b Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ "Gerald Brisco's profile". WWE. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ "Old School Wrestling – Florida results 1977 (August 10)". Archived from the original on October 29, 2006.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ "Hulk Hogan dies aged 71 after "cardiac arrest at home"". North Wales Chronicle. July 24, 2025.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ "Squared‑circle memories: When wrestling reigned in Dothan". Dothan Eagle. July 25, 2025. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "Before Hogan, there was Boulder: Hulk's beginnings in Dothan". WTVY. July 25, 2025. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "List of NWA World Heavyweight Champions – Disputed reigns". Wikipedia – list page. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ "Rock bottom: The disputed Hogan vs. Race title change, 1979". ProWrestlingStories.com. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk (2009). My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-312-58889-2.

- ^ Hogan, Hulk. My Life Outside the Ring. St. Martin's Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0312588908.

- ^ "Drive, Determination, Demandments: Hulk Hogan (Part 1)".

- ^ "Hollywood Hulk Hogan".

- ^ The Greatest Superstars of the 1980s DVD.

- ^ Hulk Hogan's WWF debut, 1979, archived from the original on April 26, 2022, retrieved April 26, 2022

- ^ "Hulk Hogan's forgotten partnership with "Classy" Freddie Blassie". The Sportster. July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ “Showdown At Shea (1980)”, *Pro Wrestling Stories*, details of matches and attendance.

- ^ “Showdown at Shea 1980”, *Prowrestlinghistory.com*, event card listing André defeating Hogan in a 13-match card.

- ^ “André the Giant–Hulk Hogan rivalry”, *The History of Professional Wrestling* by Graham Cawthon, recounting early matches including Shea Stadium body‑slam.

- ^ “1977–1983 – Hulk Hogan History”, *hulkhoganhistory.weebly.com*, listing August 30, 1980, MSG match with Monsoon as referee and body‑slam noted.

- ^ Trujillo, Alexander (October 24, 2012). "Reportaje Especial". Pedro Morales: 70 años del pionero Latinoamericano (in Spanish). El Diario Culebrense. p. 39.

- ^ "The 1st International Wrestling Grand Prix Championship Tournament". Wrestling-Titles.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- ^ a b c "INTERNATIONAL WRESTLING GRAND PRIX CHAMPIONSHIP TOURNAMENT". Wrestling-Titles.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "Wrestlingdata.com - The World's Largest Wrestling Database". Wrestlingdata. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c "10 Things Wrestling Fans Should Know About Hulk Hogan's Time In The AWA". The Sportster. December 2, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. "Nick Bockwinkel - matches - 1982". Cagematch. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ Hunter, Matt (2013). Hulk Hogan. Infobase Publishing. pp. 1, 971. ISBN 978-1-4381-4647-8. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Smallman, Jim (2018). I'm Sorry, I Love You: A History of Professional Wrestling. Headline Publishing Group. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4722-5421-4. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Carson, Johnny (July 25, 2025). "Hulk Hogan Makes His First Appearance : Carson Tonight Show". YouTube. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ "Hulk Hogan's funeral set for Tuesday in Clearwater". WTVT. August 5, 2025. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ The Hulk Hogan Archive (January 3, 2021). "AWA Hulk Hogan promo for CWF 10-08-1983". YouTube. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ Pile-driving, gut-busting, back-breaking theater - Minnesota Daily Archived October 3, 2008, at archive.today

- ^ a b Wrestling - Shining a Spotlight 12.01.06: The Rise, Fall and Legacy of the AWA. 411mania.com. Retrieved on August 5, 2025.

- ^ Hulk Hogan Archives (October 4, 2019). "AWA Hulk Hogan Interview 6-12-1983". YouTube. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ Hulk Hogan Archives. "Hulk Hogan "returns" to the AWA Interview 7-31-1983". YouTube. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ Hulk Hogan; Mark Dagostino (October 27, 2009). My Life Outside the Wrestling Ring. New York: Saint Martin's Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0312588892.

- ^ "WWF Show Results 1983". The History of WWE. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ "WWF Show Results 1984". The History of WWE. January 7, 1984. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "WWF Show Results 1984". The History of WWE. January 23, 1984. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ^ "Hulk Hogan's Overall Wrestling Skills, Broken Down In 10 Categories". The Sportster. May 3, 2025. Retrieved July 24, 2025.

- ^ "1985 Marvel/Hulk Hogan/Titan Sports Contract - Wwe - Entertainment". Scribd. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018.

- ^ "When Hulk Hogan and Marvel Collided". Red-Headed Mule. April 4, 2014. Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Someone Bought This: Hulk Hogan Vs. The Incredible Hulk in an epic battle of The Hulks!". Wrestlecrap. June 26, 2014. Archived from the original on February 11, 2024. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "The Machines Profile". Online World of Wrestling. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ McAvennie, Mike (March 30, 2007). "The Big One". WWE. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ Loverro, Thom (2006). The Rise & Fall of ECW: Extreme Championship Wrestling. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-1058-1.

- ^ "List This! Greatest Match-ups That Haven't Happened". WWE. WWE. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2016.